What finally is beauty? Certainly nothing that can be calculated or measured. It is always something imponderable, something that lies between things. — Ludwig Mies van der Rohe

900 910 is characterized by the rich community of Chicago architects and designers who have thrived within them for decades. Reflections presents occasional works about unique details and experiences in the buildings.

The Iconic Sculptures of 900 910 North Lake Shore

by Ashley Lukasik

900 910 North Lake Shore is home to an impeccably curated art collection occupying wall space in the resident hallways and common areas. Included are two sculptures by Chicago artists, Fox Box Hybrid by Richard Hunt and Earth Form by Virginio Ferrari. The sculptors shared the stories behind the pieces and how the buildings came to acquire them.

Earth Form

by Virginio Ferrari

In the early 1980’s the buildings acquired a bronze sculpture by Italian sculptor and long-time Chicago resident, Virginio Ferrari, called Earth Form. For Ferrari, this was a significant moment in which one of his favorite pieces found a home in what he considered to be the most important example of Modern architecture in Chicago–the lobby of 910.

The welded bronze piece, created in 1979, was made during a time when his work was transitioning from organic to more minimal, “I was very attracted to the city of Chicago’s architecture and Mies van der Rohe. My piece was talking about how architecture develops from nature.”

Ferrari was particularly attracted to open spaces and plazas which he says “call for art.” Moving to Chicago was part of his plan to live in a city where the “architecture is alive” and his work to be a part of it.

Prior to the 900 910 acquisition, Earth Form was shown at the Chicago Cultural Center and as part of a group show at the Arts Club of Chicago, where it was much celebrated by Ferrari’s architect peers.

Ferrari acutely recalls the day Dirk Lohan, Mies van der Rohe’s grandson and heir to his architectural firm, visited his studio. “He walked inside, he walked around and suddenly, stopping in front of Earth Form, he said, ‘I love this piece. Can you sell it to us?’ I said, ‘Why not? Where is it going?’ And he said, ‘to the 910 Lakeshore Building.’ I was very, very excited. It was a plus for me.” Once a resident of the buildings before moving next door to 860 880 North Lake Shore, Lohan led the acquisition efforts for the entire collection.

Eventually, the Mies van der Rohe Office designed a base for the piece, selecting the same Greek Verdi marble found on the lobby walls. It took a full year to find the right block with similar veins to match the walls.

Ferrari remembers meeting Mies in the year prior to his death. “I remember he told me, ‘Ferrari, normally in my buildings the only art inside is my work, but I really do like your piece.’ ”

Virginio has remained in contact with Lohan and the buildings, who hosted a tribute in honor of the artist and sculpture in 2016.

Out of his current studio in Bridgeport, Ferrari continues to work on several new projects. One is the installation of a 20 year old piece made of seven blocks of stone, each a one meter square called Crystal Formation. Each cube represents a different evolution of how crystals are formed. With the help of his sons, Ferrari is also in the process of creating a foundation to build an art center on Chicago’s south side.

Of his illustrious career in Chicago, which includes over 30 works on public display, Earth Form remains one of Ferrari’s favorites to this day. That is in part due to its’ premium location. “My feeling was that the lobby would invite you to walk inside. To participate with the space.”

Fox Box Hybrid

by Richard Hunt

“Artists must no longer imitate nature but are free to interpret it. Sometimes I try to develop forms nature might create if only heat and steel were available to her.”

— Richard Hunt

The iconic Fox Box Hybrid, sculpted by Richard Hunt in 1979, has solely occupied the expanse of lawn in front of 900 North Lake Shore at the corner of Lakeshore and Delaware since it was commissioned by the buildings under the curatorial vision of Dirk Lohan. Made of Cor-Ten steel, the contemporary abstract sculpture was designed to develop a mature oxidized patina through years of exposure to the elements—a material choice that references the merging of humanity, industry and nature. In keeping with Mies’ sleek modernist aesthetic, every detail of the piece was carefully considered by the artist.

“The problem of my sculpture involves penetration of space by line, plane and volume, as well as implications of image and emotion,” said Hunt of the overlapping elements of Fox Box Hybrid. It could be a bird or a fox with nose, tail, and delicate form, or a box. But it singularly represents none of the above.

Like several of Hunt’s other works from that time, the sculpture plays with fluidity of form and identity–not a box, not a fox but almost or a little of both. He is interested in the “metamorphosis of specific forms into hybrids,” playing with contrasts of organic and geometric, soft with hard, feminine and masculine to fuse animals and humans (RDG PDF 1989). The geometric, curvilinear form sits atop a thick pedestal also comprised of Cor-Ten.

Of Fox Box Hybrid, Smithsonian Magazine (1990) said “thoroughly modernist—but it pulses with nature and city life.”

The commission of Fox Box Hybrid occurred during the conversion of the 900 and 910 buildings to condominiums, overseen by the development company Stein & Company. After being displayed briefly on site, it was then loaned to the Art Institute of Chicago for a show entitled “One Hundred Artists, One Hundred Years.” The AIC maintains a permanent collection of Hunt’s works, and has held major exhibitions in 1971, The Sculpture of Richard Hunt, and in 2020–2021, Richard Hunt: Scholar’s Rock or Stone of Hope or Love of Bronze. Most notably, Hunt’s masterpiece, Hero Construction was given pride of place and installed permanently on the Art Institute’s Grand Staircase in 2017 welcoming 1.5 million visitors annually.

Hunt is considered to be the foremost African-American abstract sculptor. The Smithsonian American Art Museum declared “Richard Hunt’s status as the foremost African-American abstract sculptor and artist of public sculpture has remained unchallenged.” A native Chicagoan, Hunt straddled the city’s oft-segregated cultural worlds due to his upbringing on the South Side and his access to the City’s academic and artistic elite. Born during the depression in the 1930’s, Hunt studied at the University of Chicago and UIC, won scholarships at SAIC from which he graduated in 1957.

Hunt’s public works amount to over 160 and grace prominent locations in 22 states. He has also held numerous solo exhibitions and his work is represented in over 110 museums in the United States and around the world. At 86 years old, Hunt has created sculpture for nearly seven decades. He keeps a studio on the North Side of the city where he continues to make sculpture to this day.

900 910 on my Mind and in my Memory

by Margaret McCurry and Stanley Tigerman in absentia

Entering our connecting foyer one confronts Stanley’s infamous Titanic flanked by my affordable housing.

I was an impressionable teenager in 1957 when my architect father, Paul McCurry, first brought the family to visit his Schmidt, Garden and Erikson partner Vale Faro who had just rented unit 2920 in 910 North Lake Shore Drive. Christened the Esplanade with certain poetic license the two towers had from their inception become a mecca for architects. Rental apartments unlike their predecessors the cooperatives 860 880, these next reiterations by the renowned modern architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe were not only elegantly proportioned with their aluminum and glass curtain wall configured as the golden section or Phi a mathematical ratio of ancient Greek origin considered aesthetically pleasing, but with the exception of the lobby’s Verde Antique marble walls and terrazzo floors the apartments’ mid-century spartan plans and modest materials made for reasonable rent.

Sixty plus years ago standing up against the tinted glass and gazing out across the Oak Street Beach and North along the Drive the view from the “picture windows” as Mies referred to them was exhilarating. To the west the Palmolive building with its rotating beacon was the only structure interrupting our vision of the setting sun as we dined in sartorial splendor. I remember that Vale was pleased that as the first tenant to sign a lease while the buildings were still under construction, he could choose a grey tiled and fixtured bathroom versus the alternative peach.

Eleven years later apartment hunting as a fledging designer at Skidmore Owings and Merrill a firm steeped in the Miesian tradition, I remembered my earlier seminal visit to the Esplanade and learning that an efficiency apartment formerly rented by SOM for a planner brought to Chicago to design the ill fated crosstown expressway had just been vacated, I trepidatiously arranged for an interview. Weeks earlier on the advice of some of my single male associates in the Interior Design Department I had met with the middle-aged male building manager at 1350 North Lake Shore Drive, another complex with affordable studios. To my amazement as a young single woman I was told I would need to provide “good moral references” to be allowed to rent a unit. There was no way as a liberated Vassar woman of the 60s that I was going to apply to that complex with that antiquated and totally inappropriate regulation. In the office of 900 I was welcomed and offered a lease with the only stipulation that of my salary. Could I afford the modest rent? So, in 1968 with a sigh of relief, I moved into 2901 with its peach bathroom musing that maybe its first tenant was also a woman.

Little did I know that that same year my future husband Stanley Tigerman would also rent an apartment in 910 reminiscing in his autobiography, “Designing Bridges to Burn” that the building and its architect represented an aspirational measure of excellence. As a young apprentice to the architect George Fred Keck, Stanley had been introduced to Mies van der Rohe’s mentor the real estate developer of Esplanade, Herbert Greenwald. As Stanley would describe in his book, Herb befriended him and when Stanley enlisted in the Navy during the Korean war, they corresponded during his four-year tour of duty and for years afterward until Greenwald’s untimely death in an airline crash in the East River in 1959 the year Stanley left for Yale to earn his BArch and MArch degrees. As has been recorded, at Greenwald’s funeral an emotional Mies eulogized his old friend.

Metropolitan Structures, Greenwald’s successor firm founded by his attorney Bernard Weissbourd commissioned Mies in 1966 to develop an apartment complex on Nun’s Island in the St Lawrence River south of Montreal and hired Stanley who had by then opened his own office to design townhouses for the project. This assignment put Stanley in Mies’ orbit and during their first meeting in the master builder’s office at 230 East Ohio Stanley noticed that on the shelves behind his quartered oak table desk the library consisted of St. Augustine’s City of God and St. Thomas Aquinas’s Treatise on God. Stanley realized then how influential philosophy and theology were on Mies’ architecture. Stanley later wrote of the ineffability of Mies’ facades by describing how if one stood at a certain distance from them such that the edges were beyond the limits of one’s peripheral vision much like observing a Mark Rothko color field painting, the reductive, proportionally composed system of mullions subdividing glass without either beginning or end would take on an almost mythic metaphysical vision. This phenomenon is true of 900 910 but not of the “skin and bones” structural system of neighboring 860 880 where the bones are expressed.

In 1933 yielding to Nazi pressure, Mies van der Rohe, the self-taught son of a stone mason as its last director closed the Bauhaus in Berlin. He subsequently emigrated to Chicago to accept at 52 the directorship of the Armour Institute of Technology, my father’s alma mater. In 1938 Armour was housed in the Art Institute of Chicago until during the war Mies was commissioned to design a new campus for the venerable institution as it morphed into the Illinois Institute of Technology. Collecting professors for the fledging school from other former Bauhaus teachers such as Walter Peterhans and matriculating students eager to study under the master, Mies was able to set a curriculum conducive to developing his manifesto professed in the 1920’s that “architecture is the will of an epoch translated into space.” But until Greenwald became his client and mentor in the late 40’s Mies’ mantra that the innovations of science and technology should form the basis for architectural expression was only manifest in physical form in his much-publicized Barcelona Pavilion of 1929 in Spain and his Tugendhat House of 1930 in Brno Czechoslovakia.

Greenwald a rabbinical scholar and WWII veteran studied philosophy at the University of Chicago. As a realestate developer, upon the advice of Walter Gropius the founder of the Bauhaus and then director of Harvard’s GSD, the 29-year-old Herb hired the 60-year-old Mies to design the Promontory Apartment Co-ops in Hyde Park. This complex while contemporary in form is structurally reminiscent of historical resolutions with the conventional system of brick infill panels and aluminum window frames set into a reinforced concrete frame and not unlike Gothic Cathedral construction in principle the columns are stepped back as the load decreases on the upper floors.

While Promontory was under construction, Greenwald acquired the property on North Lake Shore Drive and the “Glass Houses” of 860 880 became the most publicized high-rises of the 20th Century. Constructed with a painted steel skeletal frame revealed through the supporting columns and spandrels with I-beams welded to both mullions and columns the buildings are the epitome of Mies’ edict that modern technological advances should form the basis for architectural design and construction. But these elegant clear glass buildings are not as technologically progressive as our own Esplanade. Built five years later on an ancient riverbed with a more economical flat slab reinforced concrete frame 900 910 was the first air-conditioned complex in the city. Its tinted glass is more energy efficient and its prefabricated aluminum frame is placed outside the structural form. Thus, the anodized aluminum and glass skin hangs in front of the columns obscuring them and creating that signature “curtain wall” that formed the basis for Mies’ future high rises and was vastly more influential on a generation of architects than its earlier neighbors across the street. This simplistic definition however belies the myriad proportional modes and meticulous attention to detail that comprise these paradigms of modern design giving rise to the oft quoted statement attributed to Mies that “god is in the details”.

And so cognizant of the singular status of the Esplanade I settled into my architecturally spartan but artfully furnished quarters. My sofa bed was the classic SOM tuxedo as was the walnut burled stainless-steel framed dining table surrounded by Mies’ horsehair covered Brno chairs. That first year I watched the cross braced skeletal frame of John Hancock rise to the West with its oil derrick like structure casting a stark shadow on moonlit nights. Its tapered form was SOM’s first computer aided design and it replaced the neighborhood tennis courts at Michigan and Delaware adding another controversial building to Streeterville.

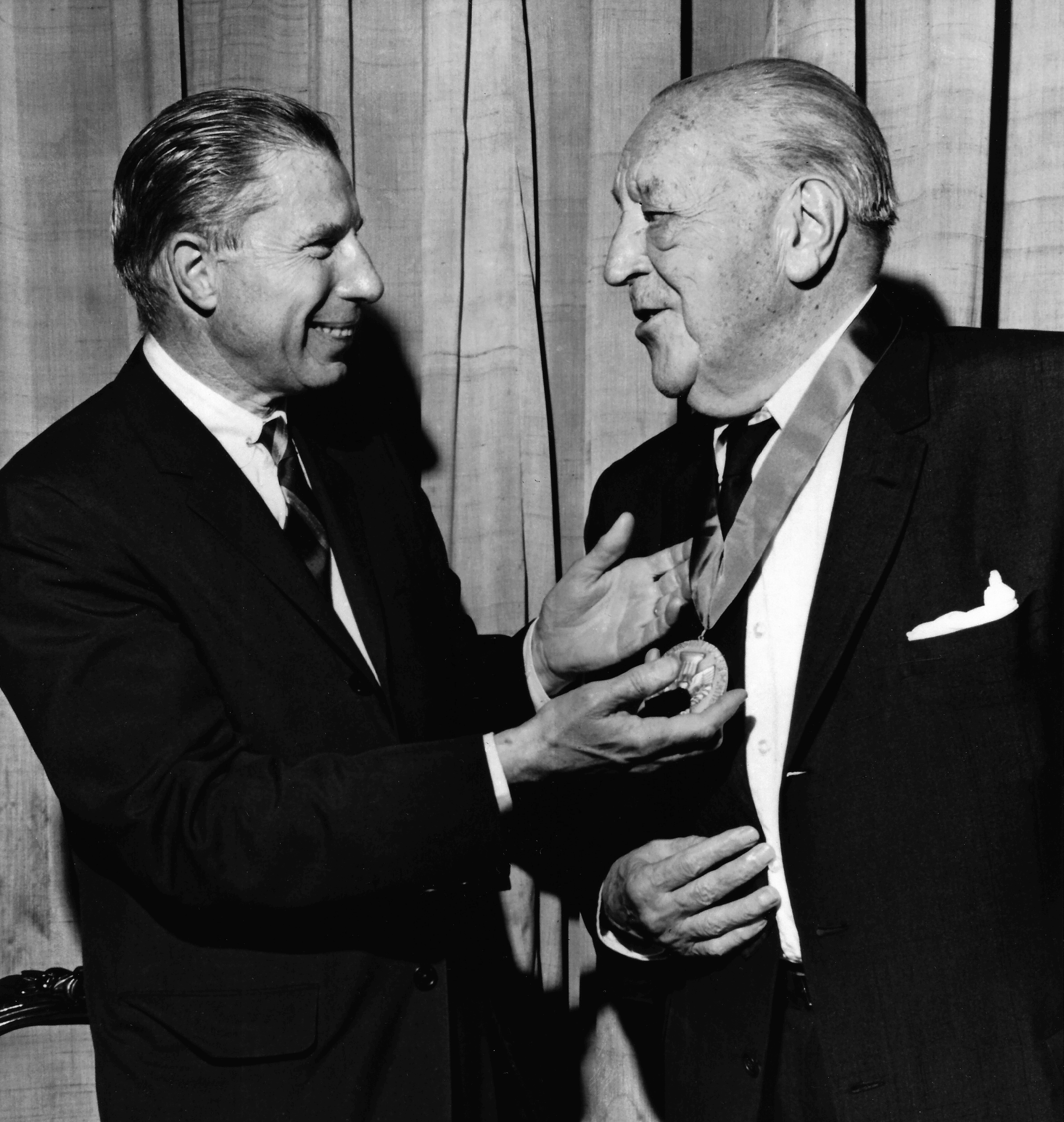

Mies van der Rohe died of cancer the following year. I attended his memorial service with my father at the funeral home in River North that has since become a part of the headquarters of the Richard Driehaus Foundation. Three years before as president of the Chicago Chapter of the American Institute of Architects my father had presented Mies with its gold medal. That ceremony was held at the Arts Club of Chicago on Ontario designed in 1950 by Mies and his former student James Speyer then Curator of Twentieth Century Paintings and Sculpture at the Art Institute of Chicago. Crippled by arthritis Mies spent his last years in a wheelchair but upon being introduced to my mother and me at the club that evening he valiantly struggled to his feet—a courtly gesture from an old-world gentleman.

Paul McCurry FAIA presenting Mies with the AIA Gold Medal.

That seminal year of 1966 when Mies received the gold medal, the Philadelphia architect Robert Venturi published “Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture.” A Princeton graduate and Fellow at the American Academy in Rome, Venturi In his polemic altered a phrase attributed to Mies that of “less is more” into “less is a bore” thus ushering in the era of postmodernism. As a reaction to the architectural pendulum swinging away from modern architecture, Stanley produced his most famous collage entitled “The Titanic” in which he depicted Crown Hall, the home of IIT’s architecture school and the most celebrated of Mies’ buildings on the campus as upended and sharply sinking into Lake Michigan. This controversial collage signaled that while Mies was still the most significant modern architect of the 20th century his sycophants were producing sterile reiterations of his famous glass houses. A copy of “The Titanic” hangs in our front hall in 910 but the original is housed in the archives of the Art Institute of Chicago. Years later as the pendulum swung back towards a form of singular modernism Miesians decreed that Crown Hall was actually rising again from its watery ashes.

Fast forward to the year 1979 when the buildings became condos and Stanley and I married. Taking advantage of the rates offered to residents I purchased 2901 and then moved across the tarmac into 2916 the one bedroom a then single Stanley had rented a few years before after abandoning life in the 19 tier. We promptly bought this unit the only one along with its neighbor across the hall that had the living room on the corner. It faced the city and with its South and West full height windows had a sunny panoramic exposure especially as with its flexible floor plate and the willingness of the office to allow renters to modify their units if they promised to restore them, Stanley had taken down the bedroom wall to expand the living room into a loft space that could accommodate his eclectic collection of early twentieth century furniture. A Stendig dining table was surrounded by woven cane Breuer chairs. Le Corbusier’s Petit Club Chairs faced Mies’ Barcelona table and his cherished parlor grand piano held pride of place across the room. However, that deconstruction left a miniscule master bedroom divided by storage units where we shared my tuxedo sofa bed which I had hoped after eleven years of duty would be retired to a guest room.

Fortunately, shortly after we returned from our European honeymoon cum lecture tour the tenant in 2918 decided to sell his modified unit. Stanley always swore that his progressive jazz piano playing had driven this elderly citizen to depart his efficiency. Many years before in another raid the current tenants of 2920 (the apartment I had visited as a teenager twenty years before), had robbed it of its two bedrooms and a bath. The remaining living room we subdivided into a master bedroom and an office with a partner’s drafting desk for me as after an eleven-year stint at SOM and having become a licensed architect under the apprentice system as had Stanley I had opened my own practice. However, my night owl drawing habits across the partition caused Stanley to advise the building manager that we would be amenable to acquiring 2915 should the occasion arise which it fortunately did a few years later. With the blessing of the condo board we were able to rent 10 feet of the corridor as a foyer allowing us to cross from one unit’s doorway to the next. Our new unit’s lake facing living room became a grand master bedroom with room for our expanding library, the furniture acquired during my SOM sojourn plus my ongoing collection of American Folk Art.

Dappled sunlight plays across Stanley’s piano set amidst our folk art and mid century modern collections.

It’s interesting to observe how this early twentieth century furniture has remained viable through a myriad of architectural meanderings. Certainly, the Miesian (designed, in collaboration with Lilly Reich) Barcelona furniture in our marble clad lobbies is a handsome counterpoint to their stately proportions. As a young man in Berlin Mies had apprenticed to architect and furniture designer Bruno Paul cofounder of Deutscher Werkbund. According to Mies’ grandson and associate Dirk Lohan who lived in 2519 at the time across from the philanthropist, Colonel Henry Crown the owner of 2520 and an early investor in the buildings as well as in IIT’s Crown Hall, Dirk suggested to Richie Stein who condoed our buildings that a fine art collection was needed for the common spaces to attract buyers. An art consultant Sondra Eisenberg was commissioned by Stein to amass this cultural trove with the stipulation that it represent the major art movements from 1950 forward. Stanley and I knew Sondra who discussed her desire to include architectural drawings with us. We were pleased when upon our advice, she acquired a John Hejduk for our corridor. Our late friend John was the Dean of the Cooper Union in New York and his original drawings were highly prized. A Richard Hunt sculpture is located on the grounds. A friend of Stanley’s, Hunt is a well-known Chicago artist whose sculpture Herb Greenwald collected as early as the 1950’s. Currently the Association’s astutely amassed collection has been appraised at many millions of dollars.

In the ensuing years many units have become combined as the relatively small-scale apartments that suited rental life in the 50’s transitioned into condo life in the 80’s and beyond. But at the same time those spare spaces made life in Streeterville affordable for young singles and fledgling families. As Director of the School of Architecture at UIC Stanley was often invited to serve as principal for a day at the Ogden elementary school located a few blocks to the west making our neighborhood a perfect locale for raising children. The deck of the car park at one time was even outfitted as a lofty playground.

As the 20th century drew to a close, our skyline slowly filled in. The old strobe light of the Palmolive building that had nightly swept across our western façade was partially shut down by conservationists stating that it’s beams blinded migratory birds. A similar fate befell the bright ring that surrounded the top of John Hancock while the northern terminus of the Magnificent Mile became “malldom” as the Water Tower and 900 North Michigan rose far above our 29th floor. To the south the rotating blades and flashing lights of a helicopter landing atop Lurie Children’s hospital have replaced the Palmolive’s nightly beacon. To the north many units formerly enjoying views of the Oak street beach have had those blocked by 990 a clumsy mass of glass and concrete that also obscures views of Benjamin Marshall’s historic beaux arts condominium on the corner.

But backed by the lake shore and set back from Michigan Ave our block creates a microcosmic community with the cultural amenities of the MCA, Navy Pier and the Newberry Library within our sphere as are all the ingredients both sacred and profane of life in a small town including significant friendships. A special one for us was with the late John Dymock Entenza the Editor of Arts and Architecture Magazine and Director of the Graham Foundation. Stanley’s mentor who had included one of his residential designs in the magazine’s influential Case Study Houses, the stately John held court every Saturday evening in the 18 tier.

Stanley died last summer at 88, but years ago chose our grave site at Graceland Cemetery. Situated on a rise it overlooks the grey granite slab that marks the grave of his hero Mies van der Rohe. As a tribute to the two unique but vastly different icons of our city whose lives Esplanade intertwined, I have asked some of the architects who inhabit the buildings to share stories and snapshots of their lives in the “Glass Houses”.

With the exception of ourselves and Dirk Lohan who lived in 910 in the seventies and now inhabits the penthouse of 880, at 92 Brigitte Peterhans’ longevity at 910 numbers forty years. An émigré from Germany Brigitte was awarded a Fulbright to study at IIT under Mies van der Rohe in 1956 the year 900/910 was completed.

Brigitte Peterhans

At IIT I also studied with Walter Peterhans and married him the following year while I was interning at Skidmore Owings & Merrill. During my long career at SOM I lived for a time in John Hancock but as I believe that the 900 910 complex is one of the most intelligent buildings in the world, I bought apartment 2716 in 1980. As befits a student of the Master and a “fan” my apartment is pristine Mies. It also houses a few pieces of original 1920’s Berlin furniture designed both by Mies and other members of the Bauhaus that my late professor husband brought with him when he emigrated from Germany in 1938.

Next in seniority among the current architects is firm founder Dirk Denison FAIA a fellow Fellow of the AIA and his partner, David Salkin of Creative Surface Design. Dirk is also a Professor in the College of Architecture at the Illinois Institute of Technology Mies’ former school and Director of Mies Crown Hall Americas Prize. The two lived in 910 for several years prior to occupying after renovating the infamous unit 2520 eight years ago.

Dirk Denison

& David Salkin

Mrs. Crown’s Bathroom dotted with Denison/Salkin’s art collection. Glass tile floors added in 2012 renovation.

This unit served as a Pied a terre of Henry and Gladys Crown, the owners of the Esplanade Apartments.

Two units on the west-facing side of 910 N Lake Shore Drive were combined and remodeled in the early 1970s, in an extravagant gilded fashion. Celadon shag carpeting, beveled mirrored ceilings, Sherle Wagner bronze swan faucets, and lace curtains tucked behind crown molding all remained as a time-capsule when I purchased the unit in 2008.

The aesthetic was in direct opposition to my Miesian training, and I delayed renovation until I met my partner, David Salkin, who embraced the mix of 1950s pure modernism and 1970s disco fantasy. Our 2012 gut renovation opened up walls, leveled floors, insulated windows, and provided a suitable backdrop for our collection of contemporary art and design objects.

However, we preserved Mrs. Crown’s Bathroom as a work of ‘Found-Object Architecture’, left several light fixtures and reorganized the existing kitchen cabinets. We then populated the open loft-like space with wood storage elements that define the master bedroom from the public spaces.

A 4’x9’ glass terrarium was later added in 2013, as we realized the only thing missing was a garden. We believe that the Miesian philosophy allows great flexibility, and the bones of the building are a perfect rational armature for a creative interior, which—in our case—is constantly evolving.

Chicago skyline view through floor-to-ceiling glass terrarium, installed 2013.

Vladimir Radutny AIA, of Vladimir Radutny Architects and his wife Yelena Spector emigrated to The United States as children from the former Soviet Union and are now raising their own children in the glass houses. Coincidently, Vladimir attended high school at the Ida Crown Jewish Academy named in honor of Henry Crown’s mother and is an Adjunct Professor at the Illinois Institute of Technology.

Vladimir Radutny

My wife and I began our life in the neighborhood in 2005, purchasing and renovating a dilapidated unit on the 20th floor of the 880 Lake Shore Drive building. In undertaking this renovation I learned a lot about the Miesian ways, reading and learning about him as an architect, a person and a myth. Never before did I look at architecture the way I began to see it after this period in time, a refined composition of thinking. I was hooked on the simple complexity of the buildings that we lived in and those that were across from us.

Unplanned, during this time, I was working at Perkins and Will in the IBM building which Mies also designed, captivating my daily life inside the modernist glass towers at work and at home. 12 years later, we are still living in the neighborhood but now at 910 Lake Shore Drive raising our 3 children. Not a day goes by that I don’t ask myself where we would live if not here, and I don’t have an answer as I would not trade the choices we made to stay here. The relationships, friendships, and memories that we created are second to none. Our home is special, as it’s a community of people that cherish the beauty of place as a common denominator. Unlike an “ideal” house to raise a family, we don’t have a back yard or a swing set, but we have special gems such as two tiers of underground parking where our kids and I go to explore during winters, we have many storage floors with long narrow corridors where I taught my children how to ride their bikes and peek inside the lockers to see what others store. We play baseball with a soft, squishy ball between the buildings so we don’t break the massive panes of glass. There are urban bunnies that reside inside the tall grasses inside our buildings sun deck, a space that most think is a swimming pool, we even buried our pet frog and pet gecko there, may they rest in peace. This amazing outdoor space that overlooks the Lake Michigan maybe the primary reason we settled here as its unlike any other outdoor common deck in the city. Its hard to explain how wonderful this space really is, one just needs to experience it to fall in love with it as many of us have.

Our apartment is on the seventh floor sharing a wall with the best neighbor one can ask for, Tony Merges has become part of our family. Our apartment doors face each other, we also share the adjacent storage rooms that only 19 and 20 tiers have. Every year on Halloween, Tony hangs the most annoying toy, a witch that screams “Happy Halloween” as one passes by it, the kids cannot get enough of it, and it’s our tenth year living in this place. Our giant windows connect us to the neighborhood and we never cover them except the bedrooms as we have nothing to hide.

From the inside of our unit we hear people outside talking or yelling, we hear horses, motorcycles and fireworks, and occasional cars screeching as they can’t make the turn along the bend of the Lake Shore Drive. I modified our apartment interior to have much larger entryways into all the bedrooms in order to borrow daylight from the perimeter windows. Our boys share one room, our daughter has her own while we have the corner with partial lake view.

Since we moved into the neighborhood, I have been fortunate to work on many apartments within the four towers, the 860 880 and the 900 910. I take great pleasure explaining to my clients and my students how the buildings are completely different from one another, showing the subtleties of material choices and the details used to refine the final outcome.

Every time that I look up at these majestic towers, I hear my children laughing in the background, “here goes daddy, looking at the building again”….

Catherine Baker FAIA a partner at Landon Bone Baker Architects and her husband Tim Kent AIA a partner at Pappageorge Haymes Partners own unit 2517 and after renting it for a number of years renovated it and moved in 5 years ago. Catherine is the former President of the Chicago Chapter AIA and is a fellow member of the Chicago Network.

Catherine Baker

Photograph by Timothy Kent

I first experienced the 900 910 buildings when I attended a gathering for Chicago Architecture Foundation volunteers back in the early 2000s. Although my husband, Tim Kent and I were in the middle of a house renovation at the time, we were both deeply affected by the grace and logic of the building. As architects living and practicing in Chicago, we vowed to live in the buildings one day.

Several years later, as our house renovation was complete and our neighborhood was rapidly changing and gentrifying, we started to discuss if we should move to 900 910. I began our unit search as any obsessive architect might – by researching every unit plan layout, unit combination and view possible! We settled on the east-facing two-bedroom ’17 tier as the most logical unit for our needs. As a testament to the flexibility of the units, I probably developed over 20 different plan variations for this one unit. And I discovered that by joining the ’17 tier with the adjacent one bedroom ‘15 tier we could create a perfect unit with a bit more room (we hadn’t anticipated how many guests would suddenly be interested in visiting and staying with us when we moved here). Fortunately, the adjacent ‘15 tier became available and we were able to create that perfect unit.

We have lived in the building for just over five years now. At first, we focused on and enjoyed the physical space of the building. We found that there is both a modesty and generosity in the design of these buildings. Originally built as a rental apartment, our unit is modestly sized and scaled. But the scale of the unit is offset by the generous views from the floor to ceiling windows and open floor plan. The first thing that one notices when entering our space is the unobstructed view of Lake Michigan. We’ve designed our space so that the furnishings are low and below the horizontal window mullion and we enjoy the ever-changing temperament of the lake (which Tim faithfully photographs every morning).

What we didn’t expect to find was the close sense of community in the buildings. Cynthia Winter and Nick Weingarten, architects and long-time residents, immediately welcomed us to the building and to their beautifully renovated unit. We discovered that their unit (when they were renting it out) was the very same unit where we attended the fateful CAF gathering years ago! We were very thrilled to have sightings of Stanley Tigerman and Margaret McCurry in the lobby or elevator. We first met Vlad Radutny and his family in the laundry room. And the sun deck has become the perfect place to social distance with other residents and guests.

I’m not sure if other buildings foster such loyalty and sense of place, but as an architect who designs housing, I am continually learning from my experience living here and I am trying to create that same sense of space and belonging in the buildings that I design.

Founding Principal of L+A Landscape Architecture Ron Henderson FASLA is a Professor and Director of the Landscape Architecture + Urbanism Program at the Illinois Institute of Technology He is just finishing a book chapter on the landscape of the campus and remarks that “few architects can organize a site as well as Mies”. Ron also just moved into 910 five years ago.

Ron Henderson

One enters 910 LSD on the city side and ascends. When I enter my residence in Tier 17, I only see Lake Michigan. The building is like a periscope—a vibrant, working city below opens up to an expansive vista of an aqueous horizon. In describing the site that would become Jackson Park, Frederick Law Olmsted observed, there is “but one object of scenery near Chicago of special grandeur or sublimity, and that, the Lake, can be made by artificial means no more grand or sublime.” 910 Lake Shore Drive is merely a periscopic instrument oriented to this sublime landscape.

Last but certainly not least are my neighbors on the 29th floor Reed Kroloff the Dean of the College of Architecture at the Illinois Institute of Technology and his partner Casey Jones a partner at Perkins & Will Architects. After living and working in many different locales, Reed and Casey moved into 2920 in 2017 and in so doing my Esplanade story which begins in 1957 with my father’s partner renting that apartment comes full circle 60 years later.

Reed Kroloff

& Casey Jones

After a long search that eliminated New York (too expensive), Los Angeles (too auto-dependent), San Francisco (again, too expensive—and, perhaps, just a bit too beautiful), and Philadelphia (too parochial), my partner and I decided to move to Chicago in 2017. Casey came out early to look at rentals: we knew so little about our adopted hometown that purchasing right away seemed imprudent. He must have looked at 50 units around town before I glanced at Redfin and saw that a penthouse apartment at 910 North Lake Shore Drive was for sale. For two people who had practiced and taught architecture for most of 30 years, the possibility of living in a Mies classic was almost as exciting as moving to the city. Casey made a rental offer to the owner, who accepted, and we were in.

Only later did we learn that staff at the famed architectural practice Skidmore Owings and Merrill had long called 900 910 (and 860 880) the “dormitories,” due to the high rate of young architects who lived there. And they were right: shortly after moving in, we encountered our long-time friends, the architects Margaret McCurry and Stanley Tigerman, standing in the hallway of the 29th floor of 910. “What are you doing here,” we asked with excited surprise, not having seen them for a couple of years. “We live here,” Margaret replied. “What are you doing here?” “We just rented the unit down the hall,” Casey explained. Stanley intoned, without missing a beat, “there goes the neighborhood.”

Not only did Stanley and Margaret live down the hall, it turns out that our friends the architect Dirk Denison and his partner David Salkin live three floors below.

We quickly ran into architects Catherine Baker and Tim Kent in the lobby. Eventually, when I started working at Illinois Institute of Technology’s College of Architecture (in an even more famous Mies building), we came to realize my colleagues, landscape architect Ron Henderson and architect Vlad Radutny, were in the building as well (not to mention even more architects and designers in 900, 880, and 860). It was like moving into a neighborhood and finding a bunch of cousins already living there.

We’ve never lived near so many fellow travelers, let alone among them. And we’ve never lived with people who are so passionate about where they reside. This must be the only place in the world where elevator talk regularly includes words like mullion, muntin, thermal break, and twin-pipe—and this is from the non-architects. The resident designers share a different linguistic camaraderie: in discussing the buildings, their hands are always shaping or tracing or folding air into imaginary forms and details that we all somehow recognize.

These conversations are delightful for us, particularly having moved here from Washington, DC, where architecture is never the subject of conversation, to say nothing of open wonderment. Perhaps it should be. In these times, we take our pleasure where we can find it, and being part of this little corner of architectural happiness brings it to us every day.